When redistributing a .NET app, there’s usually a couple of dependent assemblies (outside the main .NET framework) that go with it. These can be from a third party (e.g. NuGet packages), or they can be class libraries within the same solution. In this post, I’ll focus on the latter. I’ll show how to use the Visual Studio build process to package class libraries from a solution into an app from that same solution. The result will be a single, fully portable executable that contains all class libaries it depends on and can run from anywhere as long as the .NET framework itself is installed.

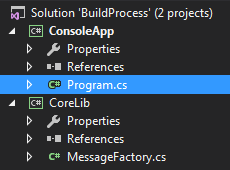

As an example, I’ll use a simple solution consisting of a class library and a console app.

The console app depends on the class library, using its message factory to print a greeting:

namespace ConsoleApp

{

using System;

using CoreLib;

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

PrintGreeting();

}

static void PrintGreeting()

{

Console.WriteLine(MessageFactory.GetGreeting("World"));

}

}

}

The message factory just contains the following:

namespace CoreLib

{

public static class MessageFactory

{

public static string GetGreeting(string name)

{

return $"Hello, {name}!";

}

}

}

If we build and run the app, everything works as expected:

D:\DEV\BuildProcess\ConsoleApp\bin\Debug>ConsoleApp.exe

Hello, World!

If we look in the output folder where the console app is built, we’ll see the app itself (ConsoleApp.exe), as well as the class library it needs (CoreLib.dll). If we delete CoreLib.dll, the app won’t run, and we’re presented with the following error:

D:\DEV\BuildProcess\ConsoleApp\bin\Debug>ConsoleApp.exe

Unhandled Exception: System.IO.FileNotFoundException: Could not load file or ass

embly 'CoreLib, Version=1.0.0.0, Culture=neutral, PublicKeyToken=null' or one of

its dependencies. The system cannot find the file specified.

at ConsoleApp.Program.Main(String[] args)

Our goal is to prevent these kind of dependencies, by packaging the needed assemblies into the app itself and having them load at runtime. This way, the executable itself is all one needs to run the app.

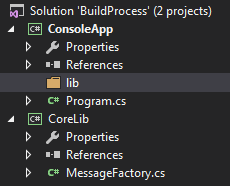

We’ll start by adding a “lib” folder to the console app project.

This is where the dependencies will be placed.

The next step involves some scripting. We’ll add the following PowerShell script called “build-post.ps1” to the CoreLib project folder:

param ([string]$targetPath, [string]$targetName, [string]$solutionPath)

$outPath = $solutionPath + "ConsoleApp\lib\" + $targetName + ".bin"

write $outPath

$inFile = (Get-Item $targetPath).OpenRead()

$outFile = [System.IO.File]::Create($outPath)

$zipStream = New-Object System.IO.Compression.DeflateStream($outFile, [System.IO.Compression.CompressionMode]::Compress)

$inFile.CopyTo($zipStream)

$zipStream.Dispose()

$inFile.Dispose()

This script takes a file (targetPath), compresses it, and places it in the “lib” folder we have just created. We’ll call this script in the post-build event of the CoreLib project, like so:

C:\Windows\System32\WindowsPowerShell\v1.0\powershell.exe -file "$(ProjectDir)build-post.ps1" "$(TargetPath)" "$(TargetFileName)" "$(SolutionDir)\"

The TargetPath variable contains the full path of the output of a build (i.e. the full path to CoreLib.dll). TargetFileName contains the name of the output file (i.e. “CoreLib.dll”). ProjectDir and SolutionDir contain the full paths to the root of the project and the solution, respectively.

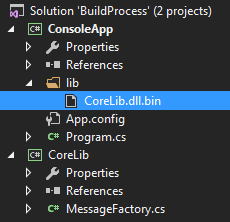

Now, when we rebuild the CoreLib project, the post-build script places the file “CoreLib.dll.bin” in the “lib” folder. We then add this file to the project, and set its build action to “Embedded Resource”.

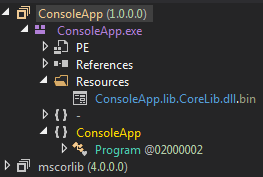

Now, whenever we build the solution, the class library CoreLib.dll is automatically compressed and included as an embedded resource in the ConsoleApp executable. We can see this if we open the executable in a tool like dnSpy:

This is great, but we’re not there yet. After all, an embedded resource isn’t just automatically loaded as an assembly for use by our app. To accomplish that, we’ll need to write some code.

We’ll expand our console app like this:

namespace ConsoleApp

{

using System;

using System.IO;

using System.IO.Compression;

using System.Linq;

using System.Reflection;

using CoreLib;

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

AppDomain.CurrentDomain.AssemblyResolve += CurrentDomain_AssemblyResolve;

PrintGreeting();

}

static void PrintGreeting()

{

Console.WriteLine(MessageFactory.GetGreeting("World"));

}

#region Assembly Loading

static readonly string ASM_TEMPLATE = "ConsoleApp.lib.{0}.dll.bin";

static readonly string[] ASM_FILES = { "CoreLib" };

static Assembly CurrentDomain_AssemblyResolve(object sender, ResolveEventArgs args)

{

var assemblyName = new AssemblyName(args.Name);

if (ASM_FILES.Contains(assemblyName.Name))

{

return LoadAssemblyFromInternalResource(String.Format(ASM_TEMPLATE, assemblyName.Name));

}

return null;

}

static Assembly LoadAssemblyFromInternalResource(string resourceName)

{

var assembly = Assembly.GetExecutingAssembly();

using (var rs = assembly.GetManifestResourceStream(resourceName))

using (var zs = new DeflateStream(rs, CompressionMode.Decompress))

using (var ms = new MemoryStream())

{

zs.CopyTo(ms);

return Assembly.Load(ms.ToArray());

}

}

#endregion

}

}

This code hooks the AssemblyResolve event on the current AppDomain. This event gets called whenever the framework tried to resolve an assembly, but failed to do so. In our example, this means it’ll get called whenever CoreLib.dll isn’t anywhere to be found when we run the app.

After the event is called, we first check to see if the assembly that’s being resolved is among the list we keep of known embedded assemblies (in this case, this list only contains “CoreLib”). If it is, we uncompress the embedded resource and load the assembly.

And that’s it! We can now run this console app from anywhere, without worrying about whether CoreLib.dll is available or not.

A few gotchas

1. The AssemblyResolve hook must be set up before any functions are called which use a dependent assembly in the function body. In our example, this means Main() cannot contain any references to CoreLib, even if the relevant lines are placed after the AssemblyResolve hook. Simply put, this won’t work:

static void Main(string[] args)

{

AppDomain.CurrentDomain.AssemblyResolve += CurrentDomain_AssemblyResolve;

Console.WriteLine(MessageFactory.GetGreeting("World"));

}

While this is fine:

static void Main(string[] args)

{

AppDomain.CurrentDomain.AssemblyResolve += CurrentDomain_AssemblyResolve;

PrintGreeting();

}

static void PrintGreeting()

{

Console.WriteLine(MessageFactory.GetGreeting("World"));

}

2. When running the PowerShell post-build command, make sure the script execution policy isn’t blocking you. If you have a 64-bit OS, PowerShell x32 and PowerShell x64 are both present and they both have their own execution policy setting.

3. The PowerShell script uses some .NET 4 features (like Stream.CopyTo). To use it, you’ll need a recent version of PowerShell. I’m using v5, but v4 should also work. You can update PowerShell by installing the most recent version of the Windows Management Framework. To find your PowerShell version, use the $PSVersionTable variable. You’ll get a table like this:

Name Value

---- -----

PSVersion 5.0.10586.117

PSCompatibleVersions {1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0...}

BuildVersion 10.0.10586.117

CLRVersion 4.0.30319.42000

WSManStackVersion 3.0

PSRemotingProtocolVersion 2.3

SerializationVersion 1.1.0.1

The CLRVersion field indicates the .NET version PowerShell uses.