I watched an interesting video the other day about the coding interview process at Google. I don’t know how accurate of a representation this is (the problem seems a bit easy), but it was interesting non the less. They have the following question:

Given an unordered list of integers and some target value, find out if there are any two values in the list that sum up to the target.

They solve it by starting out with a naive O(n2) algorithm, and then work it down to an O(n log n) and finally an O(n).

The thing that stood out for me was how rare this kind of micro-optimisation actually is in my own daily work. The systems I work with simply never face the kind of scalability stress that Google’s do. Only once in my (admittedly short) professional career have I been forced to meticulously optimize some hand-crafted custom algorithm because it needed to scale really well.

This made me wonder: when does algorithmic complexity start to matter? I’ll try to illustrate this using Google’s interview question. First off, I’ll write three implementations of the algorithm. There’s the obvious-but-naive-one:

bool DoesSumExist_Naive(List<int> values, int sum)

{

for (int i = 0; i < values.Count; i++) // O(n)

{

for (int j = i + 1; j < values.Count; j++) // O(n / 2)

{

if (values[i] + values[j] == sum) // O(1)

{

return true;

}

}

}

return false;

}

The two nested O(n) loops make this O(n2).

Then there’s an improved version that uses binary search:

bool DoesSumExist_BinarySearch(List<int> values, int sum)

{

values.Sort(); // O(n log n)

for (int i = 0; i < values.Count; i++) // O(n)

{

if (values.BinarySearch(sum - values[i]) > -1) // O(log n)

{

return true;

}

}

return false;

}

This one is O(n log n).

Finally, there’s the optimal O(n) algorithm:

bool DoesSumExist_HashSet(List<int> values, int sum)

{

var seen = new HashSet<int>(); // O(1)

for (int i = 0; i < values.Count; i++) // O(n)

{

if (seen.Contains(sum - values[i])) // O(1)

{

return true;

}

seen.Add(values[i]); // O(1)

}

return false;

}

Nothing special to any of these, but they’ll serve as an example of how the different algorithmic complexities scale under increased load.

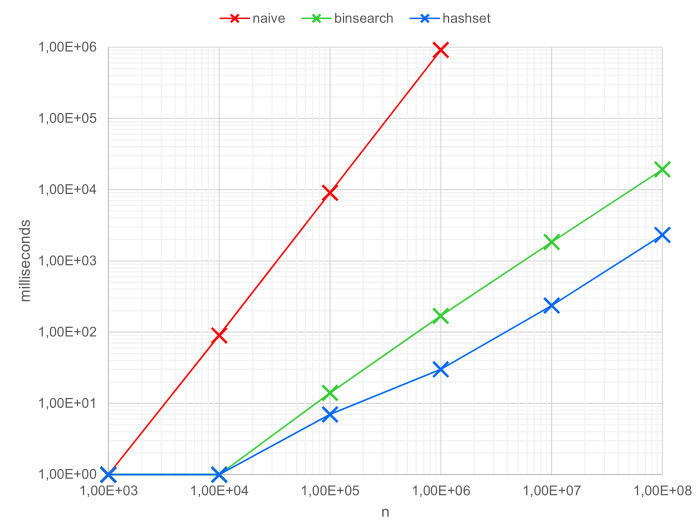

I’ll benchmark these algorithms in a worst-case scenario, by making them look for a sum that doesn’t exist. This means they can’t exit early and will have to process the entire input set. I’ve plotted the results below.

Up until n = 1.000, all three algorithms complete in about 1ms. After that, however, they quickly start to deviate. The exponential growth of the naive implementation is nicely shown in the graph: for every order of magnitude that n increases, the runtime increases by two orders of magnitude. The naive implementation takes about 100ms for n = 10.000 and a full 10 seconds for n = 100.000. At this point, both other implementations are still around 10ms. That’s a huge difference already.

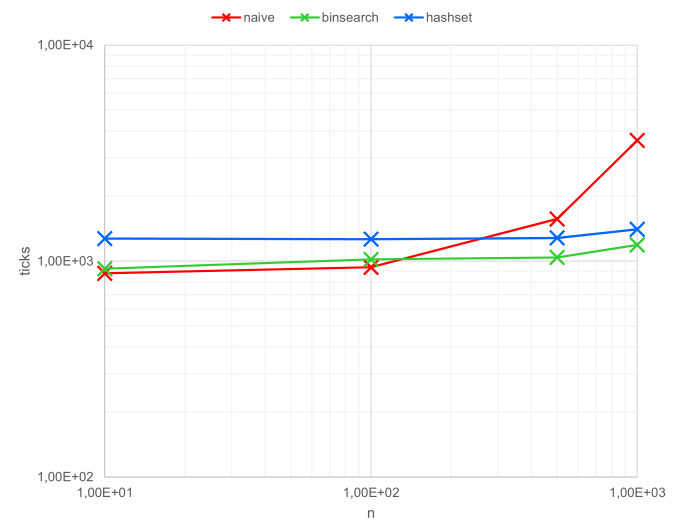

So, what now? We’ve shown that O(n2) algorithms scale horribly, what else is new? Well, I’ve mentioned that most systems I work with don’t exactly face Google-like loads, so I am actually more curious about how these algorithms perform under low amounts of stress. I’ve re-run my tests, but this time for very small numbers. The results for those runs are shown in the following graph. Note I’m measuring ticks instead of milliseconds this time.

Interesting, right? It turns out that, for small n, the naive implementation is actually the fastest. On paper it shouldn’t be, but in reality O(n) is never just O(n). It’s more like O(xn + c). There’s always overhead, and in our case the overhead of the hashset turns the theoretically fastest algorithm into the slowest for small n.

And thus we arrive at Knuth’s famous axiom:

Premature optimization is the root of all evil.

Until you know you need it, you really shouldn’t worry about these kind of micro-optimizations. Not only is it likely to be a waste of your time, but sometimes your well-intended optimizations might not even be optimizations at all…