This is a follow up to my previous post, Decoding the EU Digital Covid Certificate QR code. In that post, I looked at the contents of the EU’s international digital Covid QR code. In this post, I’ll be doing the same for the Dutch domestic CoronaCheck QR code.

The Dutch CoronaCheck certificate, contained within a QR code, is designed by the Dutch government, and serves essentially the same purpose as the EU’s DCC, namely to allow people to prove that they are “Covid-safe”. It’s mainly used by people wishing to enter venues such as bars, festivals, and other types of events. As the name suggests, the CoronaCheck certificate is intended for domestic use only, and is currently not accepted outside of The Netherlands.

It looks somewhat similar to the EU’s DCC, but its contents are quite different, as we will see. The main difference with the DCC is that the CoronaCheck certificate contains much less information. Indeed, privacy seems to be one of the core principles behind its design, as we can read right here. Yes, like the EU, the Dutch government also has been working on this project pretty much out in the open, with numerous repositories under the Ministry of Health’s official GitHub organization containing everything from design and architecture documents down to the actual source code of the frontend and backend (!) systems. This is quite impressive, and I’m really happy to see this.

However.

As wonderful as the breadth and depth of the available information is, there seems to be one crucial thing missing. Or at least, I’ve been unable to locate it in the various repositories. And that thing is the technical spec of the actual QR code. There’s numerous flowcharts showing the interaction of all of the components, the security mechanisms, basically the complete architecture of the entire system… but no easy to read spec on what the QR code—essentially the face of the whole operation—actually contains. How disappointing. The one thing I actually needed is missing…

… but don’t get me wrong, we will be decoding this thing. It just won’t be as pretty as last time.

Peeling another onion

We might not have a nice spec to read, but we still have the source code for all of the involved systems, including the verifier app that does the actual reading and checking of the QRs. Plowing through the code and reconstructing the operation of the verifier app, we can eventually figure out the decoding process. It’s not super complicated, but it does use somewhat more obscure technology wrapped in a non-standard encoding. We’ll still be using Python to create our own decoder, but we won’t have nice packages for every step this time.

Here’s what this thing looks like:

Let’s get going. Here’s the imports we’ll need for today:

from typing import List, Dict, Optional

from PIL import Image

from pyzbar import pyzbar

import asn1

import json

We start out the same way as with the EU’s QR, by just reading the raw QR data:

qr_img = Image.open('nl-domestic-covid-cert-example.png')

qr_result = pyzbar.decode(qr_img)

qr_data = qr_result[0].data

Easy. For the sample QR shown above, we find the following contents:

NL2:B4V.W9D:LWJ5W2S6A$XQ9N* Y252O4%% ZNK**$840VPY8T7$J0GR$8L2%VMO/20/3C.C.L XO:FN%IWW.TI+G3KW2RA+ $6T1 BQAGU6HJ35D.2YPIT*6Y3C733IOBZIKEWP4L/$9TX6QUVQFFZWJ+RY/JV6N3%NX%Y4XX43J182O/.AELM1%E-D*Q+8*O1CG*9/5ENUJ0HXT*PJXJ*XE-6QFMM7*B$IFEY04:-PN14PX3% Q5-JQF9$YJFVBSUD*P/AXHJRNUIA:SCX*SBIQ*BHZG$PJ+LG-S*:0.GZ8M4HO.XLM$BKZG7H/BVRUW$7WH$B3$L-T58KK$20EDRZW1B*VJ1Q5VC:X/.5*OQJ/EA92-8J*-QL6J+3NX:C5%%XZ4LLIS31KKPA9:1FP++KT:.QFRZ%M5R$I2*DM36M%BW/3.LS9MX6YE8KU4S-.Q%W2ZCI7CQ79E/X342+5T3ODK8X.-F02J-GMF18KCE.5NDV2V8I/5L0GVNPQRF+T3A*$%HI3-$R3+*RO/X8N.RG7LBFJP5SO9QAD:KYRP978DTHFL39368JXWSO2CKLQTYDZ45CF0FE9J3$$6+ZX RSNRQ6+HV%DE$V:O/Q8FYO+.NZFL6R8R8UE.0:A*Q9$8HYB+WZ26UM%.4R4 25AA7XQW.NYAJCO6+-C QZEPKLYS6G0Z/YGHPR*+YKEDO*3LE:KP HT3NCJPRNRG9K0Y84*C-7N2-BQJXY/+D-VF IIQTJ6-AV83%1Y8JMXN1I6/JSHS+HEG+VU+8UX:LL*Y%B*$G$D4H9HZVMHKWT2-87UTR+EZIWJ*IOTQ70.V%CLHVY 2-HFW4BA6-+FWIW6C:WDS /FU2I9G$LXL$B/MY*WQYMN*R00IQZJJ- 6QFX*$%-9ZGS3%G

Note that this one starts with the “NL2:” header, indicating the domestic CoronaCheck certificate. The part following the header is again base45 encoded. At this point, though, things are already going south. We can’t use our friendly base45 decoder package from last time, because the CoronaCheck certificate seems to use some kind of custom/tweaked base45 encoding that’s apparently more efficient, though it does seem to deviate from the standard. So, custom decoder it is:

def base45decode_nl(s: str) -> bytes:

base45_nl_charset = "0123456789ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ $%*+-./:"

s_len = len(s)

res = 0

for i, c in enumerate(s):

f = base45_nl_charset.index(c)

w = 45 ** (s_len - i - 1)

res += f * w

return res.to_bytes((res.bit_length() + 7) // 8, byteorder='big')

This one is derived by me from the Go reference implementation. We can then use this to decode the base45 data:

b45_data = qr_data[4:]

b45_str = b45_data.decode(encoding='utf-8')

b45_decoded = base45decode_nl(b45_str)

We are now left with an ASN.1 serialized datastructure containing an Idemix document. Fortunately, we do have a nice package to help us out with this one. Unfortunately, ASN.1 isn’t as friendly to work with as JSON. It’s a binary format and doesn’t contain any nice metadata such as the names of its various fields, instead relying on the consuming party to know the structure of the data that is being decoded. This is where we’ve had to do a bit of digging through the CoronaCheck app’s Idemix implementation, to find out what this structure is.

Here’s what the top-level structure looks like, as far as I’ve been able to tell:

{

"DisclosureTimeSeconds": "int",

"C": "int",

"A": "int",

"EResponse": "int",

"VResponse": "int",

"AResponse": "int",

"ADisclosed": "int[]"

}

It’s basically just a collection of (arbitrary-length) integers, which themselves in turn contain additional encoded information.

I’ve created a helper function to dump an ASN.1 structure to a Python object:

def asn1decode(d: asn1.Decoder) -> List:

res = []

while not d.eof():

tag = d.peek()

if tag.typ == asn1.Types.Primitive:

tag, value = d.read()

res.append(value)

elif tag.typ == asn1.Types.Constructed:

d.enter()

res.append(asn1decode(d))

d.leave()

return res

We can then pick up where we left off with our base45-decoded data, and use this function to decode the ASN.1 document and inspect its contents:

asn1_decoder = asn1.Decoder()

asn1_decoder.start(b45_decoded)

asn1_obj = asn1decode(asn1_decoder)[0]

If we dump our working sample QR, it looks like this:

[

0,

8552691641371642315207690017304824071043033037718558536544370073022402689101,

49268998317399832353736153768064371574626738522454049754099967437769709104310153609419233826877129804699795832362376712815509777453876457088841057013114352195643598128717108189839059529627445516705110559750713315964799043200407446690141492417247324685581653291574436663012628249066333485906592079172004705549,

49545515259154895522776867107959247032241047651980572443481917331143789403307139106555023968391340296360761238102083435099286993359857518,

7463954613777398261540270129601931803174222687130155761347994847425322491183229539732191198415826129672984792140024846081031144727556269931620272207040926338693607156199863455849443514025962426861121889546981280059686356901102682907001113258526002924172374302439709804314739830145508425336941142618773720272632415685260123356955161489134413604652892038340458427564488213207319660351733296444266493507445217438295664429771376840180237292580120261971321393055748802007069008017175471042800839302970504855484030669136380196262086189703554019361768087619371773861096653352702590133156777381984232268805659708171263123,

8995728107811269294519662596375119434427697506197921896277098071616873267360774813635548449786430125954107935654004828703451862806879219403683135630175078760507502448619423267753,

[

498988475518323990323119632714979941,

99,

99,

464791400517651978018913,

25707,

133,

133,

26211,

111

]

]

Not particularly illuminating, but as I’ve said, this information is in turn also encoded.

The only interesting information appears to be in the “ADisclosed” array; the remaining fields seem to be related to the security aspects of the specific Idemix implementation that is being used (“IRMA“—apparently widely used in The Netherlands?), and contain things like the document signature. The code found in the CoronaCheck repositories doesn’t directly use any of these fields or their contents.

So, let’s focus on this “ADisclosed” array, then. According to the app’s source code, it should contain the following attributes:

[

"metadata",

"isSpecimen",

"isPaperProof",

"validFrom",

"validForHours",

"firstNameInitial",

"lastNameInitial",

"birthDay",

"birthMonth"

]

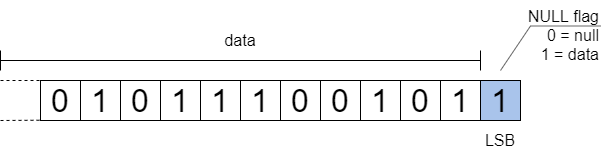

The “metadata” attribute is itself another ASN.1 structure; the remaining attributes are UTF-8 encoded strings. Each attribute is represented as an integer (as shown above), with the least significant bit acting as a null flag (0 indicating null) and the remaining bits containing the actual data.

I’ve created a class to encapsulate the CoronaCheck certificate’s contents, along with a few methods for decoding the data from the “ADisclosed” array:

class NLDomesticCovidCertSerialization:

DisclosureTimeSeconds: int

C: int

A: int

EResponse: int

VResponse: int

AResponse: int

ADisclosed: List[int]

def __init__(self, data: List):

self.DisclosureTimeSeconds = data[0]

self.C = data[1]

self.A = data[2]

self.EResponse = data[3]

self.VResponse = data[4]

self.AResponse = data[5]

self.ADisclosed = data[6]

def decode_metadata(self) -> List:

b = NLDomesticCovidCertSerialization.decode_int(self.ADisclosed[0])

d = asn1.Decoder()

d.start(b)

return asn1decode(d)[0]

def decode_attributes(self) -> Dict[str, str]:

res = {}

attrs = ['isSpecimen',

'isPaperProof',

'validFrom',

'validForHours',

'firstNameInitial',

'lastNameInitial',

'birthDay',

'birthMonth']

for i, x in enumerate(self.ADisclosed[1:]):

res[attrs[i]] = NLDomesticCovidCertSerialization.decode_int(x).decode('utf-8')

return res

@staticmethod

def decode_int(value: int) -> Optional[bytes]:

if not value & 1:

return None

else:

v = value >> 1

return v.to_bytes((v.bit_length() + 7) // 8, byteorder='big')

We can initialize this class from the ASN.1 object we’ve extracted in the previous step.

asn1_data = NLDomesticCovidCertSerialization(asn1_obj)

We are now finally ready to take a look at the data. First, the metadata. Printing it…

print(asn1_data.decode_metadata())

…results in the following output:

[b'\x02', 'VWS-CC-2']

The first part is always a single byte that indicates the credential version. Currently only version 2 is supported. The second part is a string that identifies the public key of the issuer that should be used for verification. Neither of these pieces of information is particularly interesting, so let’s move on to the remaining attributes:

print(json.dumps(asn1_data.decode_attributes(), indent=4))

This gives us the following output for our working sample QR:

{

"isSpecimen": "1",

"isPaperProof": "1",

"validFrom": "1627466400",

"validForHours": "25",

"firstNameInitial": "B",

"lastNameInitial": "B",

"birthDay": "31",

"birthMonth": "7"

}

And there we finally have it, the contents of the Dutch domestic CoronaCheck QR code. Whoohoo!

Decoding a real CoronaCheck certificate

Of course, like last time, it’s much more interesting to look at a real certificate than at a sample. And so, again, I have used the government’s CoronaCheck-app to get my own domestic QR code. Without further ado, here’s its contents:

{

"isSpecimen": "0",

"isPaperProof": "0",

"validFrom": "1629414000",

"validForHours": "24",

"firstNameInitial": "B",

"lastNameInitial": "W",

"birthDay": "",

"birthMonth": "XX"

}

The attribute names are already fairly descriptive, but here’s what everything means:

- “isSpecimen” indicates whether we’re dealing with a demo or sample, or with a live one. Thankfully, my own QR appears to be the real deal. As we could see above, the sample QR I’ve been using has this set to “1”.

- “isPaperProof” indicates whether we’re dealing with a QR that’s been generated by the app, or one that’s been printed out. The difference here is that QR codes generated by the app are only considered “fresh” for a very brief amount of time (a few minutes, from what I’ve been able to find), and won’t be accepted once expired. Paper QRs are exempt from this check.

- “validFrom” denotes the start time of the QR’s validity. There is apparently some randomness involved with this value so as to avoid disclosing exactly when someone has been vaccinated or tested, even though this really only indicates when the QR has been created.

- “validForHours” denotes how long the QR is valid for. This value is added to the “validFrom” time when determining if a QR is valid at a particular moment. For QRs generated by the app this value will always be 24 hours. Paper certificates are valid for 40 hours (in case of a negative test) or 28 days (in case of a vaccination or recovery).

- “firstNameInitial” is, surprisingly, the initial of the person’s first name.

- “lastNameInitial” is the same, but this time for the last name!

- “birthDay” denotes the day-of-month of the person’s birthday.

- “birthMonth” denotes the month of the person’s birthday.

And that’s it, that’s all of the contents. Kinda boring, actually.

In fact, what’s more interesting to me than what’s in the QR, is what isn’t in there.

- There’s nothing to indicate if a person has been vaccinated, negatively tested, or has recovered from Covid.

- For paper certificates, the validity duration indirectly reveals some of this information, but this is deemed an acceptable tradeoff.

- There’s an extremely minimized amount of personal information: initials only and no birth year. And, as we can see above, in my case my birthday isn’t even listed. According to the projects privacy considerations, any one of these bits of information (even someone’s initials) may be omitted if the resulting combination could be “too identifying”.

Even though I personally have no issues with the data contained in the EU’s DCC, I’m pleasantly surprised by my government’s apparent commitment to privacy when it comes to this design. The CoronaCheck certificate is little more than a big green “safe” sticker with the government’s signature on it, and a few minor bits of PII to correlate it to someone’s ID. Pretty nice, and a very interesting read thanks to the fact that it’s all on GitHub.

I do wish they’d have gone for a bit more standardized methods of encoding the data, instead of rolling their own base45 and then this IRMA thing that only really seems to be used in The Netherlands. Oh well. It’s still not terribly difficult to decode, but the EU’s DCC was definitely more friendly in this regard.

References

CoronaCheck app documentation: https://github.com/minvws/nl-covid19-coronacheck-app-coordination

ASN.1 specification: http://www.itu.int/rec/T-REC-X.680/

Idemix project: http://hyperledger-fabric.readthedocs.io/en/latest/idemix.html

IRMA project: https://irma.app/